Gallery

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

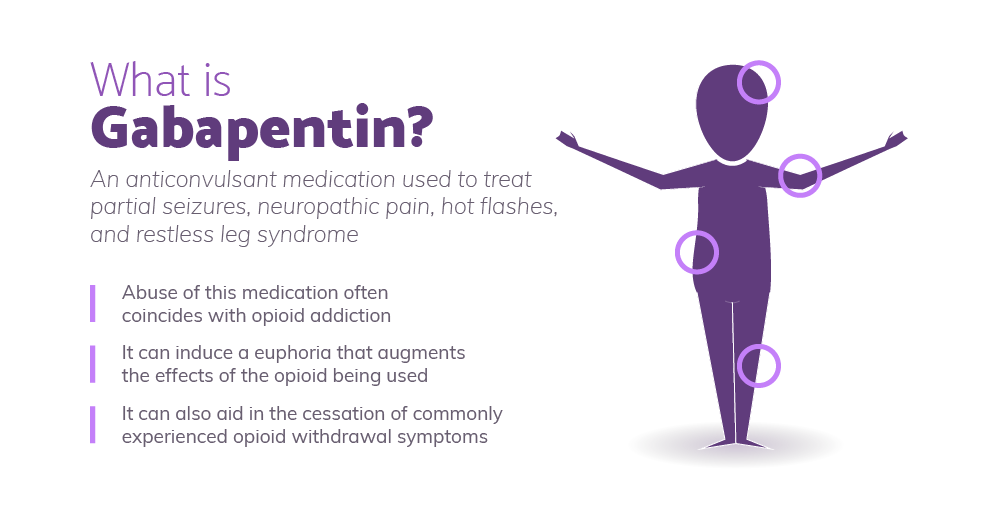

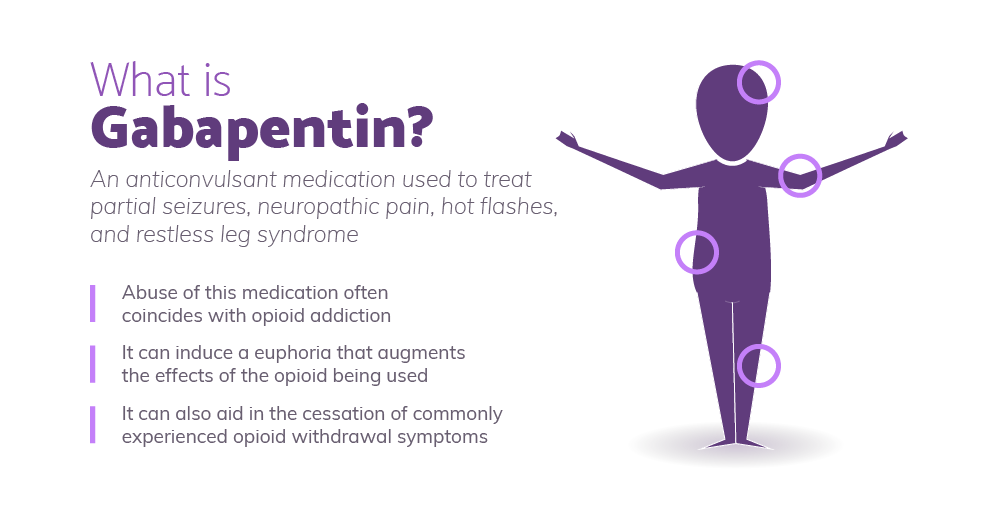

This study examined off-label use of gabapentin for psychiatric indications and its concomitant use with CNS-D prescription drugs in a nationally representative sample of ambulatory care office visits. Less than 1% of outpatient gabapentin use was for FDA-approved indications. evidence suggests that gabapentin’s use in psychiatry has de-creased over time, despite renewed interest in its potential for alcohol use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (912). Multiple RCTs have shown gabapentin to be ineffective at reducing cocaine use in cocaine use disorder. 31–34 One RCT with 99 participants with cocaine use disorder compared gabapentin 3,200mg/day to placebo over 12 weeks and found no significant difference in number of days of cocaine use, cravings, or retention in treatment. 35 Another RCT Objective: This article reviews evidence-based psychiatric uses of gabapentin, along with associated risks. Method of Research: An extensive literature review was conducted, primarily of articles searchable in PubMed, relating to psychiatric uses, safety, and adverse effects of gabapentin. Results: Evidence supports gabapentin as a treatment for alcohol withdrawal and alcohol use disorder GBP has shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence. However, the literature suggests that GBP is effective as an adjunctive medication rather than a monotherapy. More clinical trials with larger patient populations are needed to support gabapentin’s off-label use in psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders. Gabapentin is commonly used off-label in the treatment of psychiatric disorders with success, failure, and controversy. A systematic review of the literature was performed to elucidate the evidence for clinical benefit of gabapentin in psychiatric disorders. The next step was to read all of this article’s references. 2-6 Surprisingly, all 5 references focused on the relationship of gabapentin with the use of opioids or in the treatment of pain, with no mention of the common off-label use of gabapentin in various psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and insomnia. Hence, I embarked on a literature High concomitant use of CNS-D drugs and off-label gabapentin for psychiatric diagnoses underlines the need for improved communication about safety. In this nationally representative sample, <1% of outpatient gabapentin use was for approved indications. Objective: Gabapentin (GBP) is an anticonvulsant medication that is also used to treat restless legs syndrome (RLS) and posttherapeutic neuralgia. GBP is commonly prescribed off-label for psychiatric disorders despite the lack of strong evidence. Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant approved by the FDA for use as an add-on agent in patients with partial seizures resistant to conventional therapies. 4 It is an attractive agent due to flexibility in changing doses, a high therapeutic index, and lack of need to monitor serum levels. 5 As such, gabapentin has been the focus of much attention in t GBP has shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence. However, the literature suggests that GBP is effective as an adjunctive medication rather than a monotherapy. More clinical trials with larger patient populations are needed to support gabapentin’s off-label use in psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders. Objective: Gabapentin is commonly used off-label in the treatment of psychiatric disorders with success, failure, and controversy. A systematic review of the literature was performed to elucidate the evidence for clinical benefit of gabapentin in psychiatric disorders. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence for three of their common psychiatric uses: bipolar disorder, anxiety, and insomnia. Fifty-five double-blind randomised Objective: Gabapentin is commonly used off-label in the treatment of psychiatric disorders with success, failure, and controversy. A systematic review of the literature was performed to elucidate the evidence for clinical benefit of gabapentin in psychiatric disorders. Another study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry examined the use of gabapentin as an adjunctive treatment for bipolar disorder and found that it was effective in reducing manic symptoms. Despite these positive findings, it is important to note that gabapentin is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. These marketing tactics came at a settlement price of US $430 million in criminal and civil liability charges in 2004, 40,43 but led to a tremendous growth in gabapentin prescriptions for off-label use from the early 1990s to early 2000s, 40 a trend that has now shaped modern practice. 44 After the settlement, use of gabapentin for off-label Since these FDA approvals, the off-label use of gabapentin for other conditions has risen steadily. A report in JAMA Internal Medicine found that as U.S. prescriptions for gabapentin prescriptions climbed from 2006 to 2018; prescriptions for opioids leveled off before eventually beginning to fall over this timeframe. Gabapentin was not found to be effective over placebo in a comprehensive network meta-analysis of pharmacologic treatments in acute mania . Systematic reviews of gabapentin treatment in psychiatric and/or substance use disorders showed inconclusive evidence for efficacy in BD, but possible efficacy for some anxiety disorders [9, 10]. These While gabapentin is frequently used in practice for a wide array of psychiatric diagnoses, its use is evidence-based for only a few indications. Multiple RCTs have shown gabapentin to be ineffective for bipolar disorder. There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of gabapentin for MDD, GAD, PTSD, or OCD. Gabapentin may be helpful in treating alcohol use disorder and withdrawal. Between 2004 and 2010, The Veterans Affairs Department conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized dose

Articles and news, personal stories, interviews with experts.

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |